|

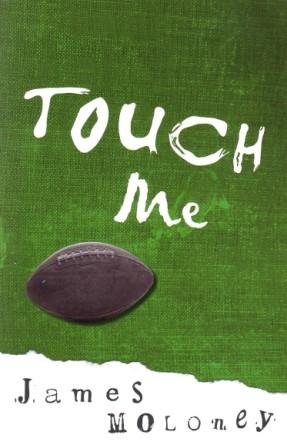

LOVE, SEX AND FOOTBALL

James Moloney

Sport is an important part of Australia’s popular culture.

Watch out! John Cleese as Basil Fawlty will spring from the nearest doorway complaining about “the bleeding obvious.” But if this statement seems so obvious, why has sport not featured more prominently in our literature for the young?

After writing my most recent novel, "Touch Me" I think I know why. Sorry boys, but sport on the page is deadly dull and I have thousands of words hacked from the early drafts of "Touch Me" to prove it. More of this later. But for now, back to sport as popular culture, the life blood of our people, a national obsession and the only thing that makes many boys get out of bed in the morning.

I was a boy once, myself, and when the State of Origin Rugby League series is held each year, I become one again. I am not the only man who finds himself animated by a boyish enthusiasm once he starts talking about sport. We could justify all this by saying that sport is good for people. It means physical exercise. But who are we kidding? Exercise! Fitness! Bah! What really gets our blood racing is the sporting contest, sport as a celebration, sport as intoxication - a release from the humdrum of workplace and classroom. Peter MacFarlane presents a wonderful picture of Australian football as celebration in his book "More Than a Game".

In writing "Touch Me", I wanted to tap into that same celebration of contest to show that there is a heartening innocence in the competitiveness that boys so often exhibit. When the reader first meets the main character, Xavier McLachlan, he is racing his best mate, Scott, to finish a set of bench presses in the weights room at school. There is no artifice, just a ferocious determination to win that brings to mind the purity of the original Olympian ideals. Unfortunately, that competitiveness can be corrupted when adult egos come into play and that is what happens in “Touch Me.”

Writing about sport, as I thought boys might like to read it, did not work, however. It is always a mistake to consider your audience too strongly. The important thing is to write what you want to say and tell the story that compels you. You would think that after six YA novels, I would have learned this. But no. I insist on going about things the hard way. What I eventually had to admit is that no matter how central a sport, in this case Rugby football, might be to the lives of the characters, no sport can sustain a story through its intrinsic appeal alone. Have you ever read every word of a newspaper report detailing the events of a football game or tennis match? No, I haven’t either. In a Viewpoint article last year, Simon Higgins wrote,” ... every time I try to emphasise technology in a story, it backlashes with twists about the human condition.”

For technology, read sport. Novels cannot be about a sport, only the players who take part. As a librarian I wished boys could understand this and stop asking me for novels about sport. They were asking me for books that gave them the same sensations as playing the game. But novels can’t do that. They are about the human condition. It was not the editor (a female) who carved all the detailed descriptions of play, tactics and the rest from "Touch Me". I did it myself because such passages were simply holding up the main game, the story of Xavier McLachlan and the unusual girl he falls in love with.

Xavier is in his final year at St Matthew’s, a private boys school where Rugby is king. There are any number of such colleges in Sydney and Brisbane and though I deliberately fudged which city it is, there may be some on both sides of the border who think it is their school. For the record, it is an amalgamation of at least a dozen schools, including one in Melbourne. The colours are blue and white, but heck, I had to choose something!

Xavier expects to win a blue jersey as part of the First XV. His identity and self-esteem are deeply rooted in his footballing ability which has not previously been challenged so when this is called into question, it seems his life is falling apart. Believe me, for some boys it is that serious. To make matters more difficult for Xavier, I introduce him to Nuala Magee.

While conducting workshops in a Melbourne high school, I came across a girl in lipstick and make-up. “How do you get away with it,” I asked.

“Oh, the teachers catch me but a few times I’ve made it through to three o’clock,” she boasted happily.

She was a big girl, what my father would call statuesque, but she wore oversized slacks and jumper which gave her a strangely intimidating size and seemed out of place with the carefully tended face. I gathered she was something of a champion amongst the girls but her motivation seemed to have more to do with stirring up the boys. Why? I asked myself. Had some boys given her a hard time?

Thus was planted in my mind the seed for the character, Nuala Magee. Nuala has been given a hard time, an experience that would crush most girls but she has the kind of determination they don’t laud on the sporting field. How she exacts her revenge is something that forces Xavier to see himself in a new light and reassess what true courage might be. There is a third character, Alex Murray, who contributes to this reassessment. Alex and what happens to him is loosely based on a boy I once knew and when you read his story, you will understand why I remember him so well.

Xavier himself has been in my mind for a decade. In as much as I was a Rugby player at school, a member of a Premiership winning First XV, I suppose there is much of me within him, as eventually I had to admit to myself there was at least a part of me in Dougy and in Carl Matt. (Or do I say that now only because I cannot conceive of their invention out of pure imagination). But Xavier’s dislocation is my own and I do remember with a clarity that frightens me, even though it was thirty years ago, how I feared losing my place in the team, because with it, I feared I would lose my place in the world.

Still, no matter how much the character may resemble the author emotionally, the clever writers make sure this character undergoes experiences very different from their own. It is a mistake to create an intense, barely disguised autobiography then call it a novel. "Touch Me" is most certainly a novel. It is a novel about stereotypes, both male and female and how they are perpetuated through sport and in life without thought or challenge. More than this, it asks why those stereotypes are perpetuated. Who benefits? Who is afraid of breaking free or seeing others break free?

It is conducted within the microcosm of a school where team loyalty and school spirit can be foisted on boys as nothing more than a herd mentality that conveniently avoids a deeper responsibility to the self and others as individuals. Not that this book attacks boys schools. In Brother Allbecker, the no-nonsense deputy and Ms Delaney, the English teacher, I have been careful to paint a positive picture. It is the insidious influence of the Old Boys in areas of narrowly defined tradition such as winning a First XV Premiership that can harm the boys - all in the name of making them men to be proud of, naturally.

But what kind of men should we be proud of? Sport only knows one kind. Xavier tries to break free of traditional stereotypes but he soon discovers why they are so powerful and what awaits those who step outside the circle. In fact, he gets off lightly in the circumstances. The hardest barriers he has to break lie inside himself and his perception of manly courage, for the worst thing about stereotypes is how easily they are internalised by the young. So Xavier thinks he knows what courage is. Footy has defined it for him and he has always judged himself by the measuring stick that football provides. But at a time when he seems to be slipping, when he can no longer measure up against the standards he has set himself, he finds a new kind of courage called for, a kind that none of his friends seem to value. There are no rule books, no coaching sessions, no drills. Unlike too many sporting stories, this one does not end with the hero returning to the bosom of his team to give his all for some higher purpose.

I do not think Xavier McLachlan is the only adolescent boy taking this journey without maps, (to steal a phrase from Graham Greene). Perhaps some of them will take heart from his story.

|

|

![]()

![]() This Web Page Created with PageBreeze Free Website Builder

This Web Page Created with PageBreeze Free Website Builder ![]()

![]()